Anja Schneider Loves Us

Time travelling through Berlin's techno past, present and future with a local electronic music legend

It’s a tale as old as time.

Two women meet over barbells at a CrossFit box a stone’s throw away from Berlin’s strikingly futuristic Hauptbahnhof built in the aftermath of the fall of the wall.

One woman happens to be a nerdy journalist who, five years ago, got addicted to the not-so-gentle art of running around screaming profanities and hurling about heavy objects.

The other, a ‘tireless creative force’ whose award-peppered and chart-topping career as a DJ, producer, radio host and record label boss lady stretches back to Berlin’s heady and defiantly anti-commercial and freedom-loving 90s heyday as one of techno’s two ground zeros.

In our sweaty, endorphin-addled post-WOD chat, we talk about all sorts of things, including the fascinating interplay between Detroit and Berlin in the early days of the genre, whether the intimacy shared between hobby athletes compares to the experience of connecting with audiences on a sticky dance floor, and what happens to local subcultures in this hyper-competitive, social-media-obsessed and über-connected world we now live in.

But most importantly, we’ll get a glimpse at what truly moves a creative powerhouse when there’s no coach screaming at her.

It’s pretty cheesy, but the art critic in me — who knows her on a personal level — would answer that question in one word:

Love.

“I’m always too excited, and too curious”

Hi Anja, thank you for taking the time to talk to me today! For our readers, can you describe exactly who you are?

My name is Anja Schneider. I’m an electronic music DJ doing techno and house music. I'm also a producer, a radio host, and have a little record label all in electronic music.

We met here in Berlin, and it's wonderful to meet you and have this chat with you.

Interestingly, just before we started this interview, we were talking about how women can be really self-deprecating, and struggle with self-promotion, compared to men. So for my next question, I’d ask you to introduce yourself as if you were a man describing his career.

If I were a man I would say that I’ve been a top DJ since 2012, traveling the world, I have this prize, I had two number one hits.

But yes, I’m just a friend from sports.

Yeah, so we did meet through sports and I think we instantly had a kind of connection. Why do you think that was?

I think it’s always nice to see a woman that is strong, and can do something better. And of course I look up to it.

Because at CrossFit Mitte, our gym, we have these wonderful, sporty, muscle men who always take off their t-shirts. But I was always looking to the girls. Like Guck mal (look) what they can do. I want to do that. Kind of like an idol.

And, of course, it’s a really nice and friendly group.

For me, when I train with someone, I always think it’s really intimate, because I show my worst side. I don’t really want anyone to look when I exercise. And so, for me, this is a really intimate situation.

So, I find it sometimes really strange if you’re not saying hello or goodbye, or not connecting with someone in this intimate situation. And I’m always trying to make jokes, like hey, ha ha, I can’t do this! So I’m always open to do this, and maybe more open in this space than if I had met you in a bar.

Would you say there's any connection with the person you are when you train and the person you are when you DJ or produce music?

I’m always connecting in the same way.

If I’m with someone, there’s always an interaction going on. So I try to connect. But, of course, there are situations where you feel like a connection is not happening, and you have to say: OK, so this is not the same vibe.

This doesn’t happen often to me. Honestly, I try always to connect with everyone, because this is maybe the only chance you have. And it’s good to know people and to open up, because you can learn from every situation you are in, and every person you meet.

I’m always too excited, and too curious. That’s why I’m so open.

That's great. So, let's scale back. How did you find electronic music?

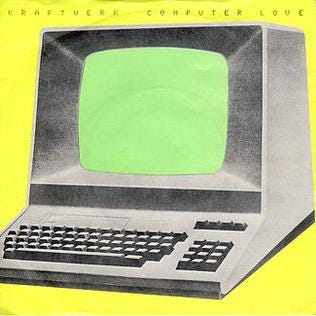

Oh, when I was a child, 10 or 12 years old, I discovered the band Kraftwerk.

I bought this album, Computer Love, which was a yellow album, and it was all computer music and electronic music. I was sitting in my childhood bedroom, and I had this Schneider Kompaktanlage, which every child in West Germany had in the 80s. It has a little record player called Schneider, which was awesome.

And I was listening to this record, and, directly, I was blown away because it was something I had never heard before.

So, I discovered electronic music and then I was a little bit more into New Wave. I was a huge fan, and am still, of Depeche Mode and The Cure, and then more industrial music.

…and you move to Berlin in the 90s, right?

In ‘93, yes.

And where are you from?

I’m from Cologne, or a little town close to Cologne called Bergisch Gladbach, which normally nobody knows about, except that there’s one top supermodel from Germany, Heidi Klum, who’s from there and this is why everyone knows this town.

So when I say I come from Bergisch Gladbach everyone says oh, do you know her? But she’s eight years younger than me, I’ve never met her.

Was there a community of fellow electronic music fans?

In Bergisch Gladbach?

No. I don’t know why I discovered it, but I could feel that it attracted me. I was fascinated by the sounds, and then I got more and more into it. In Cologne, when I was a student, I did an internship at an advertising agency. And this agency was in the same building as a record shop. Chicago Record Shop.

And every lunch I wanted to go in but was too afraid to. I heard all this cool music, and there were all these cool guys and people standing there. But of course I didn’t go in.

So I knew there was some music that attracted me, because of the vibe and the feeling of the people. And then of course, I got more and more into it, and I got into fanzines— because there was a time before the internet — and I tried to find some radio shows worldwide.

So I knew there was something going on, called techno, or electronic music, and I knew that Berlin was the hottest place. And I remember I had a free weekend. I had this little Citröen, this ‘Ente’, which was super slow. I traveled for 12 hours from Cologne to Berlin. I told myself I have to go to this club, and this one.

And then I went to Tresor, and it changed my life.

So, after this weekend, I decided to move here, and to want to be a part of this movement, this scene. I didn’t just want to consume it.

And I felt: There’s something going on. This is so important, and I want to be in there.

“DJs are not stars”

Can you explain Tresor’s significance to non-techno readers?

Of course. Tresor was the biggest techno club worldwide back in the day. The most fascinating thing was that it was underneath an old shopping centre. It was in a special room where they used to put the safes (‘tresor’ is German for ‘safe’).

There were all these little cases where they had put all the money. This was all still there. It was really dark. There was this special atmosphere. There was a stroboscope, and it was hardcore techno back in the days. It was really mind blowing, because we came out of a scene where we had discotheques and rock and roll. And normally, not parties in old buildings or in Tresor-rooms. So this is what was special about Tresor.

Can you talk a little bit more about your attraction to the scene? And do you think there are social or political elements there?

Absolutely. For me, I mean, I came from a little town near Cologne.

I didn't learn much about the world and about respect. I had no gay friends, and everyone was mostly white. And so then I came suddenly into this techno scene, and I learned so much. Everyone was the same. No one was asking what do you do?, they always just asked hey, how are you feeling? This was completely new for me.

And everyone was so open, so respectful. I mean it was the music. And of course there was a lot of drugs, which is also helpful to be open. But I learnt that no matter where you come from or who you love, so long as there is respect, and a yes or a no, anything is possible.

So this opened up a completely new world for me, which I found amazingly interesting. What was interesting was that there was no ‘macho’, no difference between women and men, and especially when I started with the techno scene. It was completely different than you might know it now.

Because we came out of this rock-n-roll scene, where there was a lot of hedonism and star-ism. And with techno, first of all, we weren’t dancing to the DJ. Because this is terrible. DJs are not stars. This all changed in the last 30 years.

But what came out of techno music was the message to be free to be whatever you wanted, to follow your dreams, to dance with the music, and to let go.

Brilliant. So I remember when I moved to Berlin, I think it was when I was 20, for a couple of months. I befriended someone who was really into techno. He was so nerdy about it, which fascinated me. And I remember him being very specific, saying techno is not actually from Berlin. It’s actually from Detroit. But how did Berlin make techno its own?

Yeah, so then we come back to the legendary Tresor club. The owner, Dimitri Hegemann, who founded the club, always had a connection to Detroit. It’s a saga in techno. For me, techno always came from Detroit.

Techno’s original inventors, Juan Atkins and Underground Resistance, always had a connection to Berlin. Because Dimitri invited them to play for the first time in Tresor. But the news said that they had gone to Kraftwerk concert in 1989 and heard them, and called it Electronic Body Music.

And so then they went back to their studios, which were really soulful, because this Detroit — the home of Motown — and then they invented techno. So I think it was a huge combination. So of course I have to say that it’s coming from Detroit.

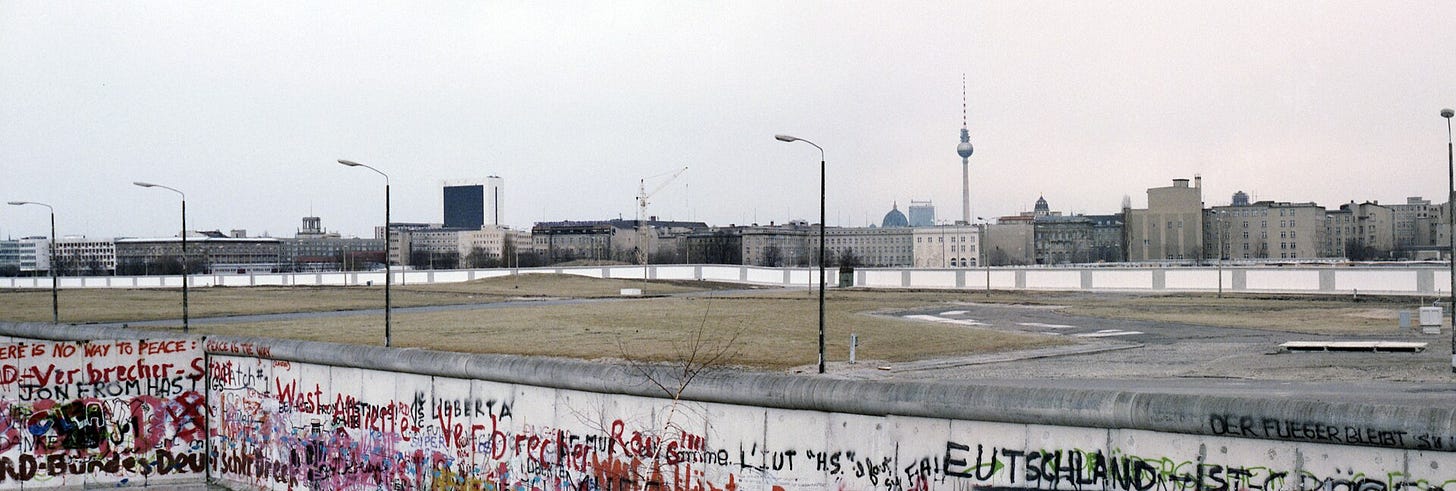

But I also have to say that it wouldn’t have made such an impact, and such a development, if we hadn’t had this political situation of the Wall coming down. Techno was bringing both of these countries together. All of this happened in Berlin. After the wall came down, there were no rules.

There were all these places in East Berlin that people had left open. So we had these amazing places where we could go in old houses and the basement of buildings where we’d build a club. And it was young people from West Berlin and East Berlin and we made the ‘Vereinigung’ (unification). And I think that also created the success of techno. Because it was the sound of the time.

The funniest thing is that Tresor was in Leipziger Platz, close to Potsdamer Platz. And it was like No Man’s Land. There was nothing there, which is why they opened the club. The first DJs Dimitri brought over from Detroit — this was already in ‘91 or ‘92 — were always asking Is this East Germany or West Germany? And of course Tresor was in the Eastern part, which didn’t exist anymore.

But they couldn’t believe it. They kept thinking; Oh my God, there’s something weird going on. So everyone told them; no, no, it’s all West Germany. So they had no idea that Tresor was based in East Germany, and also the hotel they were staying in. This was really important for them, that the hotel wasn’t in East Berlin. Yeah, it was just the American way of thinking. Like: oh my God, the Russians are still there. So we had to lie to them.

It’s funny that people from Detroit would be afraid of Berlin. Isn’t Detroit one of the most dangerous cities in the world?

It was, but it has also completely changed. It was in a really bad way. But now it’s changed and it’s a really interesting and cool city, I love it.

Have you played there?

I have. I’ve played there for Movement festival (one of the longest running dance music festivals that’s committed to showcasing authentic electronic music), and at several clubs. And for me it was always a really emotional thing to go there, because this is where everything started. So I made a fan tour to my heroes’ houses.

That’s really cute.

So, can we move forward into the present, now? I love the name of your new club night, but it’s also worth pointing out that its at Tresor’s sister venue, OHM. So in a way, things are going full circle for you. Is that right? Can you tell me more about your latest project?

Yeah, so, Tresor changed my life, and I have this beautiful relationship with Dimitri.

So after 20 or 25 years as a DJ, I came up with this concept. I still love this music. I still love going out. But I feel that my circumstances are changing. I can’t wait until three o’clock at night and go out to a club.

And I also feel like; everyone here is 20 — which is wonderful — but I can’t do this anymore. Of course I have to, because it’s my job. But for me, privately, it’s very difficult for me to go out at night.

And especially, if I make friends in my son’s school who want to hear me play, I say; Cool, come to Watergate. And they ask what time, and I say 3 o’clock. And you see these dead eyes, and know it’s not possible.

So I wanted to create a party which starts early, which is a rave, on Saturday night. Because Sundays are for professionals going to Berghain. So the party’s from 4 until 11. And so I asked my old friend Dimitri, and here I am back where everything started.

Tell me a little bit more about the music. And the event, it’s called PuMp?

Yes, it’s called PuMp, and the music is whatever we feel. For the first event, I did it with a good friend of mine. The second one included an artist from my label (Basic Instinct) who is a little bit younger. But it’ll always be house, groovy techno, and just good vibes. You’ll have something to eat, which is important, and a good wine. Because, like I said, our circumstances and points in life are changing.

I mean, we love to eat now, and drink well, and not take drugs and be wasted all the time.

And all these changes that you’ve gone through, have they affected your track-choosing process? What goes through your mind when you’re developing a track list? Is it intellectual, is it intuitive?

If I’m booked for a normal show, I’m the worst at preparing, usually. I love to arrive 30 minutes beforehand, feel the club, feel the vibe. And I know my playlist, because I do a weekly radio show.

So, once a week, I put a radio show together and then I put them into my folder for the shows. But I organise it really terribly. I have them on a USB stick. A USB stick has 6000 tracks on it. And you have to structure, organise them. And I organise them like March 2018. June 2022. Which is terrible. But yeah, if I have a show, I go beforehand, and I play intuitively. But if I have a big festival, of course I’m prepared. Or, for example, at OHM, I make a folder only with the tracks I wanted to play.

Normally I’m going with the flow, which is not always good. But sometimes when you overprepare, then you stick in your preparation and don’t see the vibe. If there are more girls, more men. Is it sexy, is it more like they wanna party. And it’s good to see this.

I can relate to that. I think sometimes if I over prepare for an interview, you risk losing the flow of the conversation, and it doesn’t feel natural.

Yeah. Genau. The same.

“I had to feed the monster”

One thing I… she says looking at her notes… I’ve obviously looked through your past interviews and how you’ve answered questions before…

One thing I’ve noticed is that you’re very brave in the choices that you make. For example, you had a big label for some time (Mobilee Records) … and you went; well, fuck it. This is getting boring. And I think, well there are a lot of people who in that situation would go; Well, you know what. I’ve made it. I’m going to stay here. What drives that?

Ah… this was, actually, the most terrible decision of my life, because I had a company that was really successful, and really big. I had eight people working on a daily basis. But, I had to feed the monster. So, I had to accept every show. I had to make hits. I had to get in the charts. And this was too much pressure for me, and I had the feeling that I was losing my creativity.

And also I have to say, I did it with a partner who was a good friend. And he had a completely different vision. He was on a business trip, wanted to get more ‘successful’. And I knew I didn’t want to lose him as a friend. But we didn’t have the same vision. So I said that I was leaving and he could take it. So we are still friends and he is running the label, and he is doing it his own way.

…and then you founded your own label

Yes, and then I founded my own label (Sous Music), which I actually did to release whatever I want, and without pressure.

I don’t have to be in the charts, and I can do whatever I want. But of course, it’s also changed a little bit. Because I also like music from different people, and I always like to support young artists. Which is always difficult, because then you have to work a lot. But yes, this is now also what I’m doing.

And I release my own tracks, and I also have a team working on it because of course I can’t do it all myself.

But it still gives me the freedom, and more freedom than I had before.

Do you think, now that you’re not watching the tracks (or are not focused on them), that that’s improved the quality of what you’re pushing out?

I would love to say I’m not watching the charts. Of course I look. And I’m also watching social media. Which is the worst thing you can do. Especially when there’s a month where you don’t have a show. So I would be lying if I said I’m completely free of this. Of course I’m not. Of course I’m looking. And of course I’m thinking I could also be in the charts. Maybe it’s human. But the pressure isn’t there anymore. I can also make it, without being in the charts. So everything is easier. I don’t have a big company. I don’t have a business plan. It’s coming more organically. But of course, I’m watching the charts, and sometimes I’m also thinking: why am I not there?

But of course, If you’re always looking at the charts, and the trends — especially in electronic music — you have a lot of trends. And I’ve seen a lot of trends in the last 20 years coming and going. Like now, you have this hardcord trend — TikTok Wave I call it — 160 BPM. And of course I’m not doing this. I could, but it would be completely stupid, because it’s not me.

So that means: never watch a trend. Try to focus on your own ideas, and what you feel is the kind of music or creativity that you want to make. And of course, maybe it won’t be successful for a couple of months, or even years. But stick to your own ideas.

That’s really important.

How did you find your creative voice?

Oh, yeah. If I had the recipe for that, I’d be a millionaire.

I mean, of course, I have to say that since I’ve started, I’ve always worked with someone. I’m never in the studio on my own. I was never so nerdy, and I can’t use all the knobs. So I always need technical help. And so for me it was always really important to work with someone, because I also love the creative interactions. Like; this is good, this is not good.

And for ten years, I’ve been working, gladly, with my husband, which is really cool. This could also be difficult sometimes, being stuck in the studio together for eight hours. laughs. But I always need someone who can help me, who I can tell my ideas to. So for example I come with an example of a song I like, or a thing that I really like in the music.

Like; I love this bass line. This is super cool. Now he knows me really well, so he knows I don’t really like melodies that much.

And normally I come with an example which I focus on, and sometimes he offers me ideas. And I always feel like if it’s an Anja Schneider track, you can hear that it’s an Anja Schneider track. But in the electronic music scene this is not that common.

Everyone has a so-called ghost producer they’re not talking about. They’re always saying oh, it’s just me in the studio. I never did this because I find it stupid. I talk to my producer and I name him in my tracks.

I love that. So let’s talk about how, in a way, you grew up with techno in Berlin. So as techno grew up, so did you. In what ways have you grown together and in what ways have you grown apart from the scene?

I think it shaped me, and we grew together in the beginning.

Of course, I learnt so much through techno. First, of course, all of the social skills. Everything being so open, easy, respectful. Musically, it was like a dreamland. It was so cool, and better of course, in the beginning. I completely absorbed it. I was working completely in techno and electronic music. This was my life. It was not just about going out on the weekends. It was my life. My vibe. How I roll.

And of course this has changed, because I’m getting older. I have my own family now. There are things that are more important than techno. laughs But I’m not one of those people who says oh, back in the day it was much better. But it’s also not really my scene now. It’s completely different. It’s harder. The hedonism is back in this techno scene, which I don’t love so much.

But I’m still happy that all the kids are still listening to this music which we kind of invented, and doing it in their own way. But have we grown together? I don’t know if you really grow together. Together is a really strong word. There was a point where I said; OK, I love this, but I won’t let this take over so much of my life.

It doesn’t define you as much?

Genau. Define is the right word.

One question I had was about how techno was recently awarded the UNESCO world heritage prize. How does that make you feel? Especially in terms of what it means as a cultural product worldwide?

Of course it means a lot. But not because of the prize or the title itself. If you look at what else is UNESCO heritage… There are some sheep in Thuringia because they are wonderful and have special hair or something.

So, yeah. The only thing about it that is helpful and meaningful is that it helps with gentrification. It helps now with building up clubs so they don’t get pushed out by rising rental costs. So this is really helpful. It gives the subculture more of a voice, and more power. This is the only advantage I’m seeing. Otherwise, it doesn’t affect me.

There were even some people from my hometown sending me congratulations. I was like; I didn’t do anything for this! And honestly, for me, it’s not important. But it does help the subculture, to get that support.

You could see that the subculture needed support in the pandemic. Because the music and event scene was completely dead. And the government had no idea how many people were working in the industry, and how many people were suffering. So, with some friends and organisations, clubs, booking agencies, we built a union, and we also went to all the politicians, and they had no clue how big the scene is, and how much money was missing because business was not running, which was quite interesting.

So it’s important that our scene’s DJs have a voice. That’s why this heritage award is really important. Because politicians otherwise don’t see the importance of the culture.

That’s a nice segue into a question I had about our influences becoming more diverse and international since the rise of the internet. And you, obviously, you travel around. You were in Ecuador last month. Do you think this is good for the scene, does it make things more competitive?

On one hand, it’s completely stupid that I travel for four days to Ecuador. Because when I was there, there were three girls taking care of me. And they were all beautiful, nice, good DJs. But of course, it’s all about festivals, social media, needing a headliner. If you don’t have one no one’s coming to your club. When I grew up, I went to a neighbour’s club and they’d play good music. I had no idea who the DJ was, but I trusted I was in good hands because of the location and the club.

Now, with the internet, and these huge festivals that always have to have big names. People won’t come otherwise. Which is sad, because it kills the local scene. Like I said these three wonderful girls. They were also good. There was no need for me to fly over. But I’m the headliner, and you know how it is. Name dropping. So I think it is really difficult.

But I also have the feeling, because after the pandemic, a lot of things changed. So we travel less now. And for me it’s even more heavy, doing this. I can’t do this anymore, and I don’t want to.

I feel you.

So, before we were talking about Berlin and Detroit, and the synergy of the sound, and also it being very localised. And now we have subcultures all around the world. For example, Norwegian metal is listened to in India. What do you think about that? Do all these influences take away from the uniqueness of the sound if it’s all coming together, or do you think it opens doors to cooler sounds?

I think, when it comes to the uniqueness of a sound, it is really separated. We have lots of genres. And this is also funny to see. Because, the internet opened up so much new music, the consumer can explore some interesting, Norwegian, whatever. Which, I never had the chance before the internet and the globalisation. And suddenly I love this special band. And this is quite interesting.

But I think that the way people consume music these days, via Spotify for example, have no idea what kind of band they are listening to with what the algorithm gives them. And it has two sides. On the one had its quite super that we’re getting so specific in music. And if you find a special DJ or a special band, this is great. But on the other hand it’s also now changing our lives.

I also think it’s still quite important to be local. But that’s easy for me to say. When I’m traveling, I meet people who say oh, you’re so lucky, you live in Berlin, there are so many clubs. And I’m like yeah, but I haven’t been to Berghain in like 10 years.

So you know. There are two sides.

This is a fun question. Do you think your job will be replaced by an algorithm?

No.

Why not?

Because DJ has become such a popular job.

Now, we have super influencers becoming DJs, models. People want to see you. And, now as a DJ you have to do certain jobs. You have to be good looking, you have to have a record deal, you have to do your own PR. And people still want to see you. Look at how this DJ culture has changed now. If you go to these big festivals, for example, Tomorrow Land, you see all these mobile phones recording the DJ, so it has changed.

But also, if something becomes more and more commercial, that gives space for a new underground, and there are always some people doing something completely crazy to go against this. So there’s always new doors.

But I can’t be replaced. As a radio host or maybe a podcast host maybe, or maybe as a producer. There’s software where you can say sound like an Anja Schneider track. But as a DJ, I can’t be replaced. People what to see you, they want to feel you.

And that can’t be replicated by a machine?

No. I’m just saying no. laughs

“I hate VIP. I hate table service. This has nothing to do with clubs”

…and as you’ve also said in previous interviews, there’s a dark side to the changes in the music industry (and the super-stardom of the DJ). You complained about the Ibiza-isation of dance music

Oh yeah, of course. At Ibiza, and everyone is standing by tables. So now in these huge clubs, with these so-called underground DJs — as I know them — they are now only getting the jobs because they are selling the tables that are like 10K per table. So there are the super rich sitting there.

And you don’t want to be with these kind of people in a club. I hate VIP. I hate table service. This has nothing to do with clubs. Just like mobile phones have nothing to do with clubs.

A club should be a safe space where everyone can let go, no one is better than anyone else, and everyone should be respected. This thing with tables and I’m sitting closest to the DJ. I have this wristband. I think it’s terrible.

And what do you think about the exclusivity of club culture in Berlin? You know, not knowing if you are ‘cool’ enough to get into Berghain, for example?

Honestly, I always had to laugh about that. Because they made it so cool. You can’t explain to someone why they didn’t get in. You can try everything. Completely black. Completely naked. Whatever. I don’t know if they even have a rule. I think they are just looking for the people, if they are feeling it or not. But they don’t really care. They are never answering to something. And this is the cult, now. I think they did it right.

And also the place. They built it before the sex positive parties. They built a safe space for gays and people with special habits. And this is how they made it. I mean, I think everyone has to be rejected for one time in their life from Berghain. It is like this. laughs

I actually managed to get in when I was 20. I think it was because I was with a bunch of guys. A couple of weeks later I tried with some girls, and we didn’t get in.

There’s no rule. A friend of mine told me — and he’s been going for years — he was told you are too sobre. And we were laughing. Like what?... I think it’s the vibe of someone. And you can feel it. For example, I played once at (fetish club) Kitkat. And I’d never been to Kitkat. Even though it’s existed for years and years. So I got a booking, and and I went. There were lots of people there who looked like they just wanted to have an adventure. Spice up their relationship a bit. I didn’t like it at all. I think that’s why they are so strict at Berghain. They want to see oh, do you live this? or do you just want to come and look at people.

I like this idea of a ‘vibe’ that you talk about. Maybe it’s not something you can find an algorithm for, it’s something that you feel. It basically comes down to connection. And I think that’s what a DJ tries to do, isn’t it?

Absolutely.

It was quite nice, seeing you at your event in April, (the first edition of PuMp), where I worked at the door, and that was super fun. I told a friend; It was one of the best days in terms of job satisfaction that I’ve had in a long time. You know, just being treated like a human being. Anja laughs.

No, but what I think was really nice was, even though you were busy working on the decks, you would just come in and bring me shots without me even asking. You were always thinking of people. It was the first time I saw you out of the context of sport. And I was like Oh, I get it. She’s in a place where she really has to pay attention to people’s feelings.

It made me think of the idea I’ve always had about true artists. That their art comes from a place of love, really. Those are dots I usually join. I’ve come across a lot of artists. And especially in the art world, there’s this grandiosity. It’s about ‘me’. You have to look at me. Whereas I feel like with anyone who actually delivers quality — it’s about ‘us’. The relationship between you and I.

Would you say that characterises your approach?

I mean it’s difficult to say yes, you said so many nice things. But, yes, I mean if you don’t have fun, and you’re not looking after people, and if they’re not having fun… in Germany we have a sentence: So wie man in den Wald hineinruft, so schallt es heraus. (how you scream into a forest will be echoed back.)

I like that. OK, so what about the future? What’s next? What are your dreams, your plans?

Yeah, my dream is to do this as long as I can.

When you get to my age, especially as a woman. You know, men, when they have their 50th birthday, everyone’s like: yeah, cool. With women it’s like; she’s still doing this? She’s still backstage. She’s still drinking, she’s still dancing. laughs. It’s always difficult. So my dream is doing this as long as I want to do it.

And at the moment I can’t imagine not to play music for other people. If there is a certain point where I don’t like it anymore, then I have to stop. But for now, I just wanna do it.

And it’s wonderful to make a living out of doing this, which is still very difficult.