The space between me, my shrink, and her piano

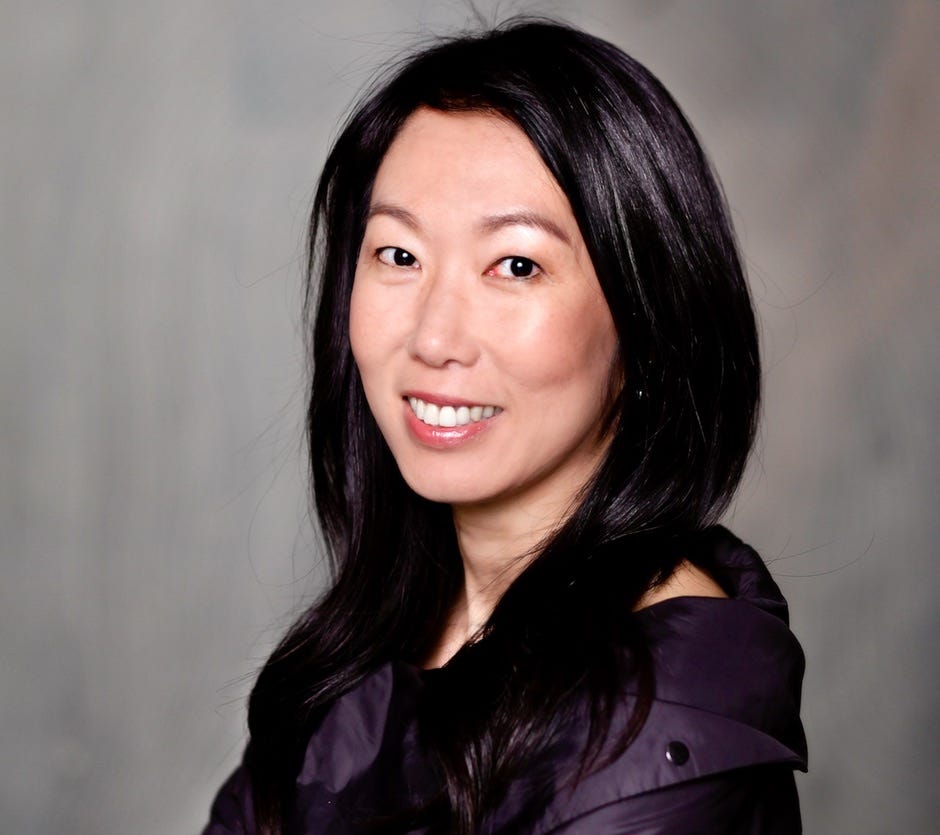

Harmony-loving concert pianist turned psychologist Heidi Tsai on the beauty of bridging worlds

Kind readers,

welcome to Inter Mundus chapter three, where I’ve asked my beleaguered and extremely good-humoured therapist to take a break from listening to me drone on about myself and tell me about her fascinating life and practice.

What makes Heidi Tsai a brilliant candidate to talk about life at the messy threshold of things? She’ll tell you herself in a bit, but the short answer is:

a) Hailing from Taiwan, she’s a globetrotting, classically-trained concert harpsichordist/ pianist who applies insights from that arduous and magical craft to her work as a therapist (and vice versa)

b) Therapeutically, she operates at the threshold of mind and body, informed by a practise called Sophrology and the physical-meets-cerebral nature of her musical career

c) she very graciously laughs at all my jokes, even or especially when I use them to bypass intimacy

d) She’s awesome

So, without further ado, here is our interview:

What is an interloper?

Hi Heidi, thank you for talking to me today. So, why do you think I approached you about this interview?

So, I’m embarrassed to admit that I had to look up the word ‘interloping’, but then I understand it now. If I understand it correctly, it means being in a place where you’re not wanted, where you’re intruding upon something, right?

That’s one meaning. I think the other one is being between worlds. Always jumping into one world, and then going into another, and not really having a fixed place, but kind of riffing on that.

(Laughs) You know, I never thought about it like that, but OK.

Well, it’s natural that you would ask me that, since I have lived in every continent and I speak five languages. And while it hasn’t really been a choice, consciously, I’ve had to move around a lot of different cultures and define myself by where I have been. So, perhaps subconsciously, I’ve tried to extend my roots in different ways.

I think I read somewhere, from a famous somebody, that musicians move through history across different social classes. That makes sense. Because music reaches everybody. I’ve managed to be able to connect with people wherever I go. Just based on what I do, people are drawn to it. So I think it’s not surprising that you’ve asked me to talk about being in between the worlds.

Can you go a little bit deeper into your interloping trajectory?

So, I was born in Taiwan. Did we ever talk about that?

Just a little bit, but, you know, I’d obviously like to hear more

Yeah, so I was born in Taiwan, and we moved to the States when I was eleven years old. I’ve been a trained musician since I was six, in Taiwan, in a Catholic school, unfortunately. And that has a lot to do with how I function as a person, today.

My introduction to piano was painful. At six my mother asked me “what do you want to do?”

Wow.

Exactly. So, I think I saw a pianist on TV, once, and I thought it looked cool. I was between that and a ticket person on a bus, because I thought that person had a lot of power, because they determine whether or not you can get on the bus. I think those were my choices.

At 11, my family moved to the Midwest. I then lived on the East Coast, after, to the Southwest, and then I ended up doing my doctorate in the Midwest again, where I met my husband, a Cellist from Spain who was studying at Indiana University.

When I finished my doctorate, he asked me if I would be interested in doing my research in Barcelona.

We lived in Spain for the next ten years. After that I thought it was time to change cultures again, so we crossed the Pyrenees, and moved to France. Throughout most of that time, we’ve been solely professional musicians, until Covid hit.

That’s when I stopped playing for about a year, professionally.

I started looking through psychology again. Since finishing my bachelor’s degree in psychology I had always wanted to continue my exploration in that discipline, but as a college graduate, I was advised to make a choice between music and psychology.

When I mentor college students now, I always encourage recent graduates to be innovative and pursue all of their passions at the same time and try to find ways to combine them. If you love math, piano, and composition, I can imagine a myriad of different ways to marry them and bring forth something original. Connecting the dots help us bridge the world.

So, if you have more than one interest, please hit me up.

Because if you need support, I will be the first to say “embrace” it, and never apologize for having more than one discipline.

The shrink in you

That’s super interesting. And when you got back into working as a psychologist, how did it feel to reintegrate that part of yourself?

It felt like I never really left it.

Classical musicians have to work really, really hard. For quite a few years, it’s eight hours of physical, mental concentration work everyday. If you don’t practice, if you don’t physically do the exercises, and sweat through it, there’s just no result.

Whereas with psychology, without meaning to, I have always used it. It’s something I naturally gravitate to, without thinking. That was how I got my degree in the first place. I ended up getting a psychology degree beside my degree in music, because I took all my elective classes in psychology. That wasn’t something I had in mind.

When I went back to it, it felt so natural. I never left it. Like, I can’t listen to someone play without delving into what that person is like. Even the way they touch the piano. I try not to be judgmental, but it’s very hard for me to not sit back and engage in some kind of research or field work about how someone is playing (or even how they bow) says about their persona.

Can you give me an example of that?

One thing that comes to mind, often, is that I once saw a pianist perform a Concerto with an orchestra. He was very popular, and he probably still is. It was Rhapsody in Blue, by Gershwin. I sat through the concert feeling so assaulted the whole time. And I still couldn’t figure out why. I mean, I love the music, the orchestra was great, and obviously he can play the right notes. So what is it about this that is making me so uncomfortable?

After an hour and a half of it, I figured it out. It’s the way he attacks the keys. I mean he’s literally hacking at them. There is no gentle side to any of it. Rhapsody in Blue is jazzy, and there’s a lot of humor and tenderness, and there’s a lot of fun, and it should sound improvised, because it’s essentially classical jazz. And this guy was just hacking away. In fact, it looked like he was just beating the crap out this very expensive instrument.

And I’m thinking to myself, “oh, my god! Is this how he treats his partner in bed?”

I’m sorry, you can edit that out.

Ha ha, no, we’re keeping it.

Ok, well, because that could be sexy, for maybe five seconds, right? I mean, sometimes, that might be fun. But for an hour? It just kept going and going. And, as an audience it was so much to take, and got boring after a while… I felt like the music, his musical persona, the composer, and me as a listener, were all separate entities, there was a big disconnect in the whole experience.

Now, that is a very personal experience. He got a lot of applause. This may be an insight into how I relate to musicians and music as a listener. I cannot remove that part of me. This is how I experience music, and teaching. I say this to my students: “You can produce the same beautiful sound without all that extra anger. And if you want to do it in the part where it’s appropriate, then that’s fine. Your instrument is your ally, treat it with love and respect.”

It’s a physical relationship between the musician and his or her instrument.

Bringing Bach Back

So, we’ve talked a little bit about the way psychology weaves itself into your music. Can we now look at how your musical identity impacts your psychological work?

I remember watching a video of you talking about Mozart, and how you had researched his mental landscape and how he would approach his own music. And that being more important to you than bringing yourself into the performance…

OK, so I am going to use Bach as an example. Because for many, his music is considered very cerebral. I think he is a genius. I am not religious, but his music, and himself, and his life, and his devotion, would be something that could convert me over any Bible, priest or preaching.

This is how much power Bach’s music has on me, personally. Because so much of it is sacred. And I think, very often, musicians feel -- and have been trained -- to play music having to bring something ‘original’, ‘creative’, to it. I think in the process of believing that, especially to Bach’s music, we ruin it. At some point, Bach is no longer the most important thing in that music. We become the most important thing, and what it is we do to it, to make it ‘original’ -- to make it our own.

I understand where this impulse comes from, because there are so many recordings of every composer. But, I also believe, that just by being a woman, an Asian woman at my age, having gone through my experiences, and that, at this moment, playing a piece of music that has been played for 200 years, composed by a dead white man who had like, thousands of children, I am bringing, without conscious intention, something original to his music.

When I’m approaching a new piece of music, I don’t ever think that I have to bring in something ‘extra’. It’s just the way I interpret it. Like, when I read a book, it’s been read by everyone. But when I read it, the book has been rewritten again. So even if a piece has been played by everybody, I still go in with the trust and belief that I am bringing something (without trying) that’s original, that’s creative, and that’s interesting for another person to listen to.

The danger is we listen to recordings a lot, and we try to imitate people. And this is why everything sounds the same. So, now you’re in that same conundrum of ‘well now we have to bring something original because everything sounds the same’. So, we should just not listen to thousands of recordings or the same recordings over and over again, and then try to replicate that. After all the research we can read on a composer and the historical context, we have to go inward, and think about how we see it.

Facing you, facing me

Does this attitude you bring to your music translate into your work as a psychologist?

Yes, so I’ve given my practice a new word. It’s relational.

I was thinking, what stays me in everything I do?

It’s that I trust that, just by relating to the person, being me, we learn a lot from each other. And I’ve certainly learned a lot from you. You’re one of my longest-standing clients, and I really appreciate that connection. The things we talked about made me think about many things about you, but also about me and how I am in the situation when you’re talking to me. And this is the same with students who come to me wanting to learn the piano or the harpsichord.

I always ask them to play something, but what I really want to find out is “what is it that you want to do, and what might be blocking you from doing so?”

I’ve had teenage boys who have said “nothing, it was perfect!” And I reply with, “OK, if you think it’s perfect, that is OK. But I can tell you what are the possibilities out there. How else it could be?”. And you can still say “that’s fine I still want to stick to this way,” then I’m not going to sit and argue with you about that.

I don’t try to fix things. Someone from non violent communication once told me it’s literal violence when you make someone do what you want them to do. And this could be emotionally or physically, including imposing your objective. I think that’s pretty fair. There is a moment when you are ready, and you are really ready. And I can sense it, and you can sense it. And I can hold your hand, and in your case I can hold your hand online, and go through this process. I can be there when you fail, and I can be there and encourage you, but I can’t make you do it. And it’s the same with piano.

So, what joins the dots with all of this is my relating to you. Likewise, I can relate to the music of a composer, and what the intention was. And I will never impose. I try to understand. I try to adopt and combine my voice to what I think he or she had in mind. Which I think, on a good day, I can do it. That’s the goal at least.

What is Sophrology?

Super interesting. As I said before we did this interview, I didn’t want to make it about me, but I do think it’s worth saying here that one thing that attracted me to you, initially…

Oh, please, let’s go into my comfort zone.

No, what I didn’t want to do with this piece is centerise myself. There’s a bit of a trend in journalism at the moment of that, but that’s not what I wanted to do here.

But what I did think was important to mention was that, while I’d done traditional ‘talk’ therapy before, what you offered was something a bit more mind-body oriented. At the time I was exploring the topic of anxiety and PTSD, on a personal and journalistic level, and how it can manifest physically and that’s what brought me to you and your practice. The logic went as follows: talk therapy, which I started with at 25, had really helped in feeling understood, and understanding myself in a cerebral sense, but didn’t seem to give me robust enough tools to deal with the more visceral symptoms, i.e. panic attacks, intense emotions, mystery aches and pains of PTSD, along with panic-related writer’s block. A journalist’s stagefright equivalent, I guess. Getting really into sports, delving into the world of MMA and Crossfit at the ripe old age of 29, gave me a much greater sense of control over my own physical reactions to ‘triggering’ events. It become clear that my particular healing journey would have something to do with lining up the body and mind, so that when my mind races, my body isn’t left in the dust somehow. That’s how I found you and your practice.

What we ended up doing, over the course of eight weeks, was a series of physical exercises - everything from kicks and punches to other more joyful actions, each with an ‘intention’. We also finished off our sessions with meditation.

Can you tell me a bit more about this practice?

So it’s called Sophrology, and I’m certified in France.

It’s essentially a self-regulating somatic practice that aligns our objectives with our body, mind and behavior. Its exercises have mixed origins from deep breathing, tai chi, massage, Yoga, guided meditation, hypnotherapy, and positive affirmation. I don’t call it therapy, I don’t like to use that word. I believe that 95 percent of the time, there’s nothing to fix. And I would always need 99 percent of your participation to make this work. Also, I don’t believe I know more about you than you.

It’s the same with my students, no matter how young they are, I would never allow my clients to think I know more about them than they do. But what I try to do is unclog, or unblock anything that had been natural for us as humans, to learn, which throughout the years became blocked through some experience, so that new information can’t come in. And as you know, as academics, we’re very cerebral. You are an amazing example of someone who goes out there and does physical things, and combines all sorts of fun stuff, to balance that out. But what I would say is where you find yourself most at home, is when you’re thinking, and putting your thoughts onto paper. I’m the same, and that’s what got me looking into sophrology in the first place.

So how did you get started?

It all started during Covid. I decided to start from body upwards, because there was so much time. So the first thing I started doing was meditating. Trying to connect my body to every moment, then I would follow my daily meditation by learning a new Bach fugue during the confinement. This was my core support during the entire Covid shut down in 2020.

I found the whole routine so nourishing and grounding, I invited a group of people to meditate with me on Whatsapp daily, as well as a group of colleagues around the world to learn the entire Book I of Bach’s Preludes and Fugues (WTC I). It was a way to connect with people around the world through our mental wellness, as well as through music. For now, if I don’t get to meditate, I feel like there’s something missing throughout the day.

Because I was spending so much time reading about psychology and joining online conferences again during this quiet period when there weren’t any live concerts, I chanced upon Sophrology as one of the popular practices in French speaking countries. I know many high schools offer Sophrology for students as a way for students to lower stress and concentrate on exam preparations. Its philosophies aligned with my own daily practices, so I decided to learn more about it and became certified as a way to lift others.

My practices have also been heavily influenced by the Polyvagal Theory by Dr. Stephan Porges. He proposes that the evolution of the autonomic nervous system provides the neurophysiological substrates for adaptive behavioral strategies. The theory links the evolution of the autonomic nervous system to affective experience, emotional expression, facial gestures, vocal communication, and contingent social behavior. Simply put, our physiological memories can affect how we react to future experiences, but there are things we can do about re-setting those physiological memories. For instance, providing trust and compassion in a relational space to flush out or replace previous experiences or voids.

Now, what I found with you is that while meditation really works with a lot of people, I did notice that you got increasingly anxious, and I could see it, I mean even online. And then I thought to myself -- that was one of the things you taught me, actually, that we can do this again, where I increasingly see you get more anxious, or I can go with you. And I can see where you take me. Because we tried it my way, let’s try it yours.

And then we had a break (from therapy), and then when you came back to me, you said to me specifically, “I would like to keep in contact in another way.” And then what we talked about was me witnessing: me relating to you as me, providing a space filled with attunement and active listening.

You suggested I act as ‘life coach,’ and I said that I couldn’t coach you on how to live your life, but I could accompany you, and witness what you go through, witness your emotions and function as a reflective mirror. Of course I’m not just a mirror. It’s relational. But if you can feel safe with somebody, for an hour a week, perhaps this can grow, and this can multiply to another person, or perhaps a whole group of people.

Because now you’ve practiced feeling safe with someone, accepting advice from someone. It matters that you had that freedom to not take my advice. But anyway, thanks to you, I realised that, just like in music, not every method is for every student, and not every student is for every practice.

So, you gave me an F in Sophrology?

Ha ha, no not all.

I’m too neurotic for Sophrology.

Ha ha. No, I thought, I could be stubborn, and say “nope, we’re going to continue to do this”. And I am going to, either manipulate you or muscle you into meditation, because that’s against my own nature. So I went with where you wanted to go. And I think in your case, it was the better choice. Not saying one day you wouldn’t transform and be that person, or close your eyes and feel a second of peace, that that might come another day.

But at that time, I didn’t think that was a thing for us. But I could provide you stability. Somebody who doesn’t change according to you. I think I remember telling you, when we were in Berlin that one time we met, we were talking about anger, and I said “it’s OK for you to be angry at me,” and you said “and you too, you can also be angry at me.” But I literally can’t. That would just be really wrong.

So, my job is to provide you with the place where you can be angry. And you can be sad. You can be whatever you want to be. I was surprised that you thought it needed to be a reciprocal thing. That I let you be angry, so you let me be angry. You see what I mean about the safe, relational thing? I am willingly providing a space for you unconditionally. So if you’re angry at me, that space doesn’t move. And that gives the space a strength.

Because otherwise it's kind of wobbly. Like, if I thought “I was angry at you, I don’t understand why you can’t take my anger,” that would make that space really unstable.

The stories we tell ourselves

Yeah, so we did sophrology together for a while, but when I came back to you, I wanted us to have a more talk therapy-style approach again. But what was still helpful there was the insight you provided that came from sophrology.

I remember you pointing out my tendency to quickly rationalise and drill down on a topic while missing the bigger picture.

You gave an example of a tree. If I notice it only by marking down the word “tree”-- because that’s what comes quickly and easily to me as a verbal person -- I won’t take the time to notice its colours, how it smells, how it feels.

Yeah, but that is why it’s important to have someone to reflect on, because first you do need to sound it out instead of just having it in your head. First you have to be able to form it into words, sound it out, someone hears it, and for that person to pick it up and reflect it back. So this is super awareness. And you can do it on your own, but it’s really, really hard.

But yeah, we all have a narrative, we all have a story.

But the cool thing is that those stories can change. Because we’ve done some work on that. Our future is really based on our stories. Because we can live the same stories over and over, and we hold on to those stories like a lifeboat, because it’s what has kept us safe until now. But if we let go and just try to swim a little bit, we can hop on a different boat (the boat being the story, of course), that maybe the present will change. It’s both really really hard, and insanely easy. Literally just, a change of mind.

I think we’ve had this exercise before, about walking around.

The exercise is that when you’re walking around, while you’re in your head. And the default is, we don’t know what other people are thinking. Even if we think we do, we’re assuming something, you know, that, they’re judging us or whatever.

But if we purposely replace that with eye contact that holds a little bit longer, and a smile, and sending a positive thought, or, assuming they’re having a good thought about us, if you can achieve that, all of a sudden, your steps are lighter, you’re smiling, and then people might react by smiling back, and that feedback makes you happier. It’s a very simple exercise. So, if we trust that other people have good intentions for us and we have good intentions for them, our lives are better. I’ve been told that that’s naive. And it is true, there are people out there to con me, of course there are.

But for me to go through the next part of my life thinking that, I think it’s a choice I won’t make. So I can choose either way, and neither way is assured, right? They’re both assumptions. So I choose to assume everyone has the best intentions.

This goes the same for being on stage as well. Because one of the things about stagefright is that you are thinking about what people are thinking about you, when really people are just thinking about what they are going to have for dinner. But you’re up there, and you’re vulnerable. And somehow you immediately go, oh this is right, that’s not right, I did this wrong, or something. Or we can assume that people are willingly choosing to be there together and we want the best out of the experience and wish everyone well.

So you can totally rebuff this question if you want.

You talked about the stories that we tell ourselves, and the power and the hindrance they bring. Can you give an example of a revelatory moment for you from your personal life?

Yeah. OK. So, the concept of abandonment.

I can’t think of one single person who might not have an abandonment issue. Some more than others. But I never thought of myself as one. But that’s funny, because, given my own history from my family. So my mother was a single mother who had to work a lot to provide for me, and that is her form of love, and just because she doesn’t say certain things to me doesn’t mean she’s abandoning me. It also means that she’s never had the same care that I’m looking for from her. So she’s literally, physically unable to do it, not that she doesn’t want to do it, but because she maybe desperately needs it herself.

Now, while it’s not my job to mother her, I can have compassion and empathy towards her. Did understanding all this change the dynamic between myself and my mother? Not to the extent that I would love. But the door has opened for me, at least. I feel like the door, somehow, is cracked for her, but it can always be bigger. Especially the more I see her.

I just saw her, as you know, a couple of weeks ago. And every time I see her, I feel that door move. On a good day it opens a little bit more, and on a bad day, she shuts it completely. I am reminded that there is an abandonment issue, but I know deep down, that it’s not a current issue. That she’s not currently abandoning me. And it’s OK that I have these feelings. So I reframed the story. And, you know, some people prefer the door to never be opened, but for me, if you want to get closer, the door needs to be cracked, at least, to know that there’s something more on the other side. And when both parties feel safer, you can walk through it, or stick a hand in and reach out.

Is that what you wanted?

That’s beautiful. Thank you.

A musical metaphor

So, what’s next?

One of the things I’m doing now is working with corporations, especially the ones who hire a lot of expats. I am trying to combine my experiences as a musician to help improve team work by using connections similar to chamber musicians on how and when to lead and when to follow. To use a musician’s mentality to help a team, aligning intent with our behavior, gesture, words, and emotions.

How would you define a musician’s mentality?

In this case, the mentality of a chamber or orchestral musician: The most optimum mentality in question here is contextual, the ability to see the entire picture, or hear your place in a symphony. Let’s say you’re a double bass player, or a violist. When you get your music you have one line. Like eh, eh, eh. And if you don’t play it right you will screw up everyone’s part, even if no one hears it. If you can’t see the contextual reason why you are playing that line, you might feel “what I do does not matter. There are twenty violists next to me”.

But if you have studied the score, and you see your part in this huge Mahler symphony, and that how you do your part has a direct impact on say the violinist sitting next to you, then you will go in with a different attitude. Even how you take a breathe before your entrance has an effect on those next to you. You see your function in a larger context.

My favourite example is a string quartet: There’s nothing, in my opinion, that’s more harmoniously in balance than a string quartet, because there’s no piano in it. When you add a piano, Immediately, visually, it’s out of whack. But if you just have four string players, and if they are really in tune with each other, that is, for me, what harmony and world peace should look and feel and sound like.

When I was an undergraduate at Boston University, the Muir String Quartet did the entire cycle of Beethoven String Quartets throughout the year. I couldn’t understand why I was so drawn to them. And until this day now, I’m still very drawn to that texture, and it’s because it’s so balanced. Four people moving as one -- it’s so beautiful, and the sound blends.

A string quartet -- that’s my holy grail of world peace.

Do not quote me on that.

Why not, it’s a lovely quote!

It’s so tacky! OK, well, is that OK as an answer?

Yeah, it explains your philosophy. And it brings all the strings together. Oh. Pun not intended.

Thanks for your time, Heidi. It’s been a pleasure as always.

If you want to learn more about Heidi, do check out her website.

That was great. Really had the sense of you both in the room